History of Art in a day

I am addicted to city life; constant activity, tangible possibility, creative energy teeming on every corner.

I experience it all fully cognizant of two different realities in society- one for those with the capital and influence to indulge in anything they like, and one for the rest of us who only barely manage to scrape by; but the magic of such a convergence of individuals in a democracy is that there always seems to be another option, an alternate path to the same wonder and amazement. My years in New York City were full of standing-room-only tickets to operas, cheap local theater, long lines for lotteries, and free admission days to art exhibits. All of this primed me for broke backpacker life in Europe, and led me to a plan of Icarean ambition on a February Sunday in Paris: The Louvre, Musee D’Orsay, and Le Centre Pompidou, all in one day- the monthly ‘free admission’ day for Parisian museums.

That would be the largest art museum in the world, the largest collection of impressionist art in the world, and the largest modern art collection in all of Europe. From 8am - 10pm. For free.

Staggered closing times dictated my schedule, but I intended to follow a mostly chronological history, from ancient artifacts in the bowels of the Louvre to mixed-media pieces created in the past month for Le Centre Pompidou.

If I even managed to make it out of the Louvre, that is.

After an hour inside, I was fairly certain it would be impossible for any human to comprehensively explore this labyrinthine museum in a full lifetime, let alone a day; my half-day timeframe was a laughable pittance compared to its expanse. I did embark on a fruitless search for Vermeer at one point, but I generally settled into my limited prospects and experienced what I could- an overwhelming abundance nonetheless. Stunning works awaited at every turn; 2500 year-old Greek monuments and palatial Mesopotamian frescos adorned ordinary staircase landings, almost contrivances amidst an embarrassment of riches.

Once I made it to a wing full of ancient engravings and illustrations, I forced my mind to slow down, strip away extraneous thoughts and focus on the objects before me: functional containers, coins, weapons and jewelry decorated by human ingenuity. I marveled at the sheer effort it must have required with only simple tools and time-consuming processes. Even the oldest artifacts we have of early human civilization included such artistic extravagance alongside reasonable functionality; I thought of Werner Herzog describing a prehistoric cave-drawing of an 8-legged bison as our first “motion picture” in his documentary ‘Cave of Forgotten Dreams’, an example of our capacity to render a perspective of time into a single image- even tens of thousands of years ago.

Was there something innate in human consciousness that led to imaginative symbolism and evocative aesthetics? Did prehistoric people, more closely attuned to the natural world, actually perceive reality differently than us- as vibrant and ‘magical’ as the mythologies they left for us? Perhaps rigorous adherence to science has limited our capacity to perceive reality in similar ways, or perhaps a deluge of media has worked to distract our imagination and encourage addiction rather than nourishment.

I don’t know. In a way, the human accomplishments in front of me felt alien; relics from an era I cannot comprehend, from a reality I can not perceive. But they were also deeply resonant, aspirational in a manner that felt familiar to me. Every design, every flourish, every pattern searched to ascribe meaning to the world; through reflection, or subversion, either forcing order on chaos or accepting organic order. Sometimes it was enough to simply decorate a small trinket; sometimes it drove humans to create extraordinary monuments to supernatural deities. Thousands of years later, they are fatefully all put on display together for strange humans like me to ponder.

From the antiquities I passed into vast sculpture halls, where the human form was celebrated and glorified on increasingly grander scale. I circled round the famous, armless Venus de Milo, a sinuous and bare work of art that only hints at its original appearance or intended subject. Its shape and mystery are equally alluring, and have captivated audiences here for almost 200 years since its accidental discovery on a Greek island; were the people around me as struck by this mystery as I was? Did they choose a single possibility and settle on that imagined world? Or did they see a simple piece of stone that someone else told them was significant? I guess there is no correct answer here- or perhaps they are all correct answers. And maybe that’s the ultimate beauty of art: every perspective, every answer has merit. Even the artist does not control the ‘meaning’ of their work- every single human who engages with it must also have a piece of that meaning as well. Each work is one physical creation with an infinite number of realities and ideas. This broken feminine statue has no clear author or history, yet has been celebrated and regarded by hundreds of millions of people with distinctly different stories and reactions.

...much like life, perhaps?

The museum was jam-packed by mid-morning, thronged with opportunistic tourists like me. I passed stone walls from the palace’s own medieval origins, preserved for hundreds of years. They were dutifully constructed as a fortress for their time, and now they are venerated as works of art in their own rite. Babylonian friezes awaited me next, more decorative practicalities from their own time eons ago. I continued through history and sculpture, until I found myself under a towering bronze statue of the Greek Titan Atlas, with a preposterously large globe balanced on his back; my own puny body was dwarfed and humbled by the weight of his grand scale.

And then I was somehow in the middle of a life-sized replica of French living quarters from the “beautiful century”, a gilded age of renaissance and ostentatious luxury- at least for a few- that eventually saw the transformation of this palace into a museum, as art became celebrated differently. The very walls and ceilings of the various rooms I traversed echoed this change, as ‘art’ became an all-encompassing backdrop; every element and every object seemed to have ornamental qualities. The apogee of this mentality was the Galerie d’Apollon, a ‘room’ of such incomprehensible splendor that I completely ignored the precious jewels ostensibly featured in the middle; I was utterly overwhelmed by ravishing detail on walls, floors and vaulted ceilings. It is the most gloriously ostentatious room I have ever experienced. I couldn’t help but stand and stare, mouth agape as I pored over richly-saturated paintings, golden trimmings and exquisite stucco sculptures. People streamed past me imperceptibly as I stood frozen in the center of the room, unable to move on. Painted depictions on the curved ceiling above seemed to lift me off the ground and into their dramatically realized heavens, mythic and legendary. Virtual release from human life below. Every element of the halls shone with the same rapturous intensity, a light I could not differentiate as it blessed us all. Was this ultimate escapism, or ultimate glorification?

I don’t know, but it felt I could linger in that room for an eternity.

I continued into the world of paintings next, not humankind’s first foray into manipulation of color- too delicate to withstand the ravages of time- but the Renaissance flowering of new methods, techniques and elements, innovation in pursuit of past glory. A different wave of excitement percolated; sculptures and artifacts of the ancient world inspire a colder, more reflective and intellectual admiration in me, and the release of fuller spectra enchants me to no end. My eye is always enticed by the most colorful piece in a room first, before I can take in what else strikes me. I didn’t have much trouble in these wings of the Louvre; nuanced masterpieces lined every wall, crying out for each of us to enter their vivid world. I visited Dutch landscapes under infinite shades of grey and soft violet; I entered darkly-lit French tales of sin, passion and punishment; I joined crowds at luminescent Italian scenes of history and lore; I traveled multitudinous realms in the span of a few steps.

The Coronation of Napoleon stopped me in my tracks again, though; I sat on a small bench, perfectly centered, and gazed up past dozens of humans into its massive domain. It is 10 meters high, yet feels even more expansive every time you focus on one detail, one spectator out of its hundreds. It is lit as if God himself directed the scene, which is I imagine what Napoleon himself wanted everyone to think. As majestic as it was, I also had to admit that oppositional nature; this was propaganda, after all, for a megalomaniac.

But then again, you could say the same thing about every piece of art commissioned by a monarch, or the Church for that matter.

A half an hour later, I somewhat mindlessly followed the flow of people to the gravitational center of the museum's fame: the Mona Lisa.

The scale was reversed here from that of the Coronation of Napoleon; a mass of humans crowded to this comparatively small piece of art, like paparazzi around a worldwide celebrity. I stood at the back of the room first and watched as each person fought to get to a better vantage point- but almost none of them were looking at the painting. In fact, I don't think I saw a single person engage with the portrait for 5 uninterrupted seconds; the purpose for everyone was a picture. A selfie. An announcement that they had been there, had accomplished the feat of 'seeing' the Mona Lisa. Like there was an accepted, universal scavenger list, and they had heroically checked this item off of the list.

Did any of them actually experience anything? Did they wonder what it was about this decorated canvas in front of them that had beguiled the world? What was the point of all of this, if it was just a mental exercise? Did they feel anything, experience anything in this real moment, apart from some virtual reward?

Maybe I was too judgemental. Maybe I misread their demeanor, and believe things about art that are too fanciful. Everyone's perspective is valid in some way, right? I already wrote that down.

Eventually I bounced my way to the front, just as I had practiced in college house parties and club crowds before. A couple of bouncers guarded the portrait from behind a rope line, and people snapped and chattered relentlessly; but I slowly drifted into Da Vinci's world.

I don't know what makes art 'great' in the academic sense, and I can't explain why this is a masterpiece. But I know that when I stood still, relaxed my prefrontal cortex, and let my eyes take in every blush of color...I was bewitched.

Though its spectrum is not wide, subtle shades seem to shimmer incandescently; there are no hard lines, but accumulations of light, or darkness. The landscape behind is almost suggestively expressed, a mythic background. She hovers in front, a vision both mathematically perfect and unspeakably ethereal, with eyes turned askance and lips enigmatically curled. Each corner, every trace belied meticulous care and intention. My appreciation only grew with each passing moment, as hungry patrons jostled for their selfie space.

This felt like the peak of my Louvre tour, I knew; the day was beginning to slide away from me, and I still had two (!!!) voluminous museums to explore. I reluctantly exited the palace, crossed the Seine in late afternoon sunlight, reached the Musee d'Orsay and realized for the first time in my 72 hour Paris visit that I was in the wrong time zone. I never adjusted after leaving London, and somehow managed to go three days without any inclination...which goes to show that I was either wonderfully absorbed into my Parisian excursion, or just another hopelessly ignorant American.

No comment.

Luckily, I was still able to enjoy an abridged experience. And I did not need any additional adrenaline from time-sensitive urgency; the moment I entered the era of impressionistic and expressionistic art, my heart exploded once again. The Renaissance brought a life-like vibrancy to pictorial art; these two movements electrified that vibrancy and burned down every formula and convention in search of what the essence of ‘art’ was, or could be. If you could strip away every label and guardrail passed on by tradition, how would you express the same formless concepts we all encounter?

The answers posed by Monet, Renoir, Cezanne, Pissaro and every other artist here thrilled, challenged, enchanted; each one repeatedly took my breath away. They were consciously painting inner worlds, exploring the space between objective reality and unbound perspective. For them, the truth of a moment was not found in meticulous re-creation but in amorphous subjectivity, in uninhibited expression. It wasn’t about what a scene looked like; what did it feel like?

Monet is one of my favorites, in a hopeless cliche; every one of his works seems to portray how my spirit interacts with the world, how I feel when I watch a sunset or listen to a river; the way nature seems to vibrate with more energy than my eyes can perceive. Each broken brush stroke conveys a small piece of the whole, just as each detail in my field of vision has an interior world, a truth that interacts with every other detail to form a grander universe of truth. His collection of works here spanned most of his adult life, and told a story of constant experimentation, evolution, and dissatisfaction with what art was 'supposed to look like'.

Renoir’s ‘Bal du moulin de la Galette' was the work that entranced me the most; I had never seen light conveyed with more magic, or more honesty. The static scene somehow felt full of motion, engaged in a perpetual dance before my eyes. It was completely free; rather than a sealed world beckoning my entrance, it fought against its frame and radiated outwards. As if it capture life, not form. My heart raced within my chest, itself barely bound by reality.

But out of all the artists and creators in this wondrous, grand museum- a former railway station that still retains its vaulted, humbling character- the artist who struck at the center of my soul was Van Gogh.

Is, Van Gogh. Everything I write about Monet and Renoir and their movement was true of him, too, but to an ecstatic degree. And I think it is his palpable presence that produces this effect; his strokes sing with passion and boldness, unafraid of being seen or judged. Somehow his colors vibrate more, in an unexpected harmony of competition; the pointillist characteristics I recognized were invaded by assertive lines and uneven textures, given new meaning by these elemental clashes. Every one of his works sent a new wave of chills over my body; I tarried in his rooms for as long as possible, until security guards gently pushed me away at closing time.

I slowly drifted out of the museum in a happy fog, each step a weightless exercise, and meandered to another monumental work of art, the Notre Dame cathedral, against a dusk sky of gorgeous purple adorned by luminous full moon. The picture could not have been painted more perfectly; alas, two years later I would find myself watching flames consume the cathedral on tv.

Finally, I arrived at the contemporary world: Le Centre Pompidou. Rather than accepting traditional form, the building itself is a postmodern work, literally inverted with functional tubes and escalators displayed outside rather than contained within, just as the ancients turned function into art.

On the ground floor was a featured exhibit, a retrospective of an artist I did not recognize. The exhibit was housed in one large room, with objects arranged in an irregular pattern around the floor. A sheet was handed out at the entrance, a map of the exhibit with objects numbered in the order we were meant to follow- but without and obvious logic or connective thread. We were largely meant to work it all out in our heads, piecing the puzzle together for ourselves. After all my inner condemnation of the perfunctory nature of engagement with the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, in the most modern of art here I was forced to do...a scavenger hunt.

Welcome to the future, I guess? The objects were a mixture of media forms; some sculptures, some...random industrial materials? Two television screens played loops of experimental video, and there were also stacks of magazines and newspapers that contained pictures and articles, that I suppose were connected in some way; I appreciated the mental exercise, but was also torn between my own imagined meanings and what the grand plan behind it all may have been. Was this what art had become, the logical endpoint of historical study and obligatory innovation? Or was the ultimate meaning here that there was no meaning at all?

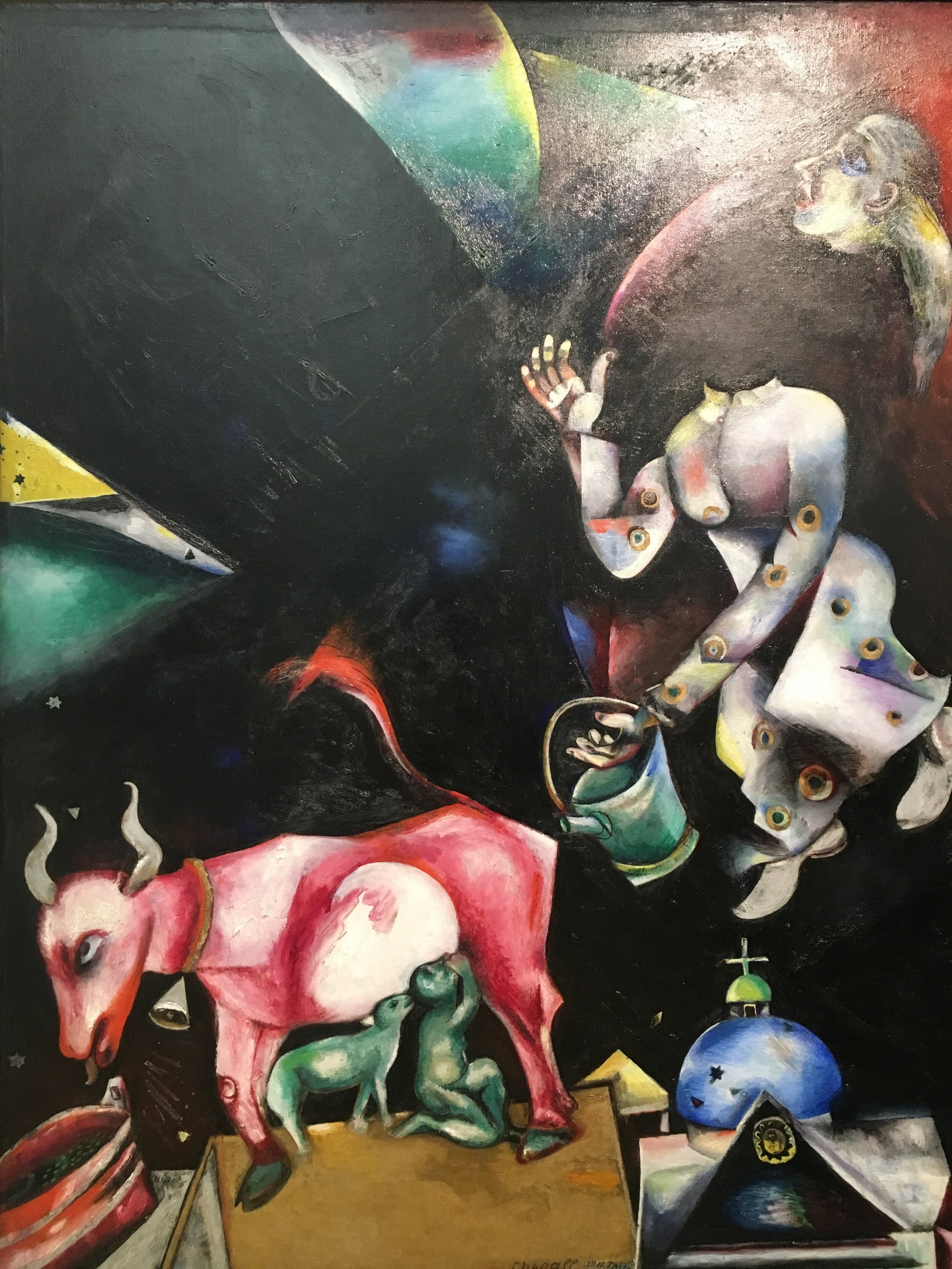

I don’t know. I left the exhibit in somewhat of a daze, at the end of a long day of rumination and mental shifts. I spent the rest of the evening in more traditional exhibits that covered the space between early 20th century expressionism and contemporary puzzles; an era of surrealism, pure abstraction, and deconstruction- the works of Picasso, Dali, Kandinsky, Chagall and others who carried the boundless freedom of Impressionism into experimental Avant-Garde. These works stirred my soul again, employing color, geometry and subject matter to challenge my perspective and provoke deeper contemplation. Whereas the bold beauty of the Musee d’Orsay incited intense emotional response, the masterpieces of this age constantly induced more reflective contemplation: why? Why did the piece make me feel a certain way? Why did the artist make these choices? Why does it work- or, why does it not?

This was what I needed after the previous cold intellectual exercise; a reminder of what Art can still mean, of the ways it can still prod us towards personal growth. The final piece I absorbed as the museum closed was the most powerful of all: a contemporary wall-sized mural of Europe, the Meditteranean region, Near East and Central Asia, graffitied by crude drawings and words, with hundreds of threads connecting Paris to every corner of the map; a dense flow of ideas and people from around the world to this single epicenter, self-styled capital of Art and Culture. Outside this museum, debate raged on what Western Europe should owe to the rest of the world; desperate immigrants were dying in accidents at sea or stuck in migration purgatory as they sought the supposed land of opportunity and liberty. But the connecting threads of this mural deliberately employed no arrows or intended direction; they extended evenly in both directions, with the implication that the exchange of culture has never been a one-way avenue. The great movements in art I had experienced today were influenced by every region, by countless different cultures and ideas. Paris was Paris not because of its inherent French-ness, but because of the often contentious clash of outside perspectives- difficult, painful clashes that spurred growth and progress.

We are who we are today because of those conflicts; and to me, there is no more exquisite representation of this truth than what we call ‘Art’.

As if to drive that point home, my day did not end with this art piece; I went back to my temporary home in Montmartre, to an Irish bar where I watched that most American of exports, the Super Bowl, with a room full of fellow transplants in the middle of the night. I was exhausted, but as luck would have it this wound up being perhaps the most exciting Super Bowl ever- where the Patriots came back from 28 points down to beat the Falcons in an Overtime epic that ended just in time for me to pack my things and catch an early-morning train to the Alps a full 24 hours after I had joined the line for the Louvre.

Just another day.